Designing artifacts for Conversational UI

Here at Carbon Five, we’re pretty fascinated by bots and conversational UI. Recently, we worked with Cooper to test and launch a new Alexa skill, a meeting manager to help teams run daily standups. We’ve already written a fair bit about our collaboration process in general, and in the following post I’m going to get into the nuts and bolts of how we design, plan, and document a user’s conversation with a bot.

Between our work on hands-free applications, our project with Cooper, a handful of Slack bots we’ve built during hackathons, and a Facebook Messenger bot we built to celebrate May the 4th, we’ve had a few chances to experiment with ways to create a conversational UI script.

With a traditional, graphical UI (or a “GUI”), it’s relatively easy to represent a user’s flow through a product. One screen leads to another screen and to another. Any interactions with the product are represented as states on those screens. The resulting design artifact is mostly linear and easy to visualize and parse.

However with a conversational UI, and especially with a voice UI that doesn’t offer any visual aid, representing the user flow as a design artifact gets tricky. Conversations are rarely linear. Users can change the subject, say the wrong command, or just choose to stop talking, and the user flow needs to account for this. Unlike with a GUI, which might disable buttons or force the user to answer a question on a form before continuing, a conversational UI can’t force the user to say or do anything in particular. Unless the conversation is entirely linear, with only yes or no answers, mapping a conversational UI can quickly become complex.

Additionally, conversational UIs are a new paradigm for most users, and they can sometimes have unrealistic expectations of what a bot can do, or embody it with attributes it doesn’t actually have. Without a visual UI to make it clear to the user what actions are and are not possible, there’s a risk that users can get lost or confused about what to do next.

An effective conversational UI diagram should not only represent the multiple paths that a conversation UI can take, but also represent the various states, inputs, and outputs inherent with any interface. Most importantly, the format needs to be updatable and developer friendly in order to be truly practical. Below is a breakdown of some of the methods Carbon Five has experimented with to produce design artifacts for conversational UIs.

Script

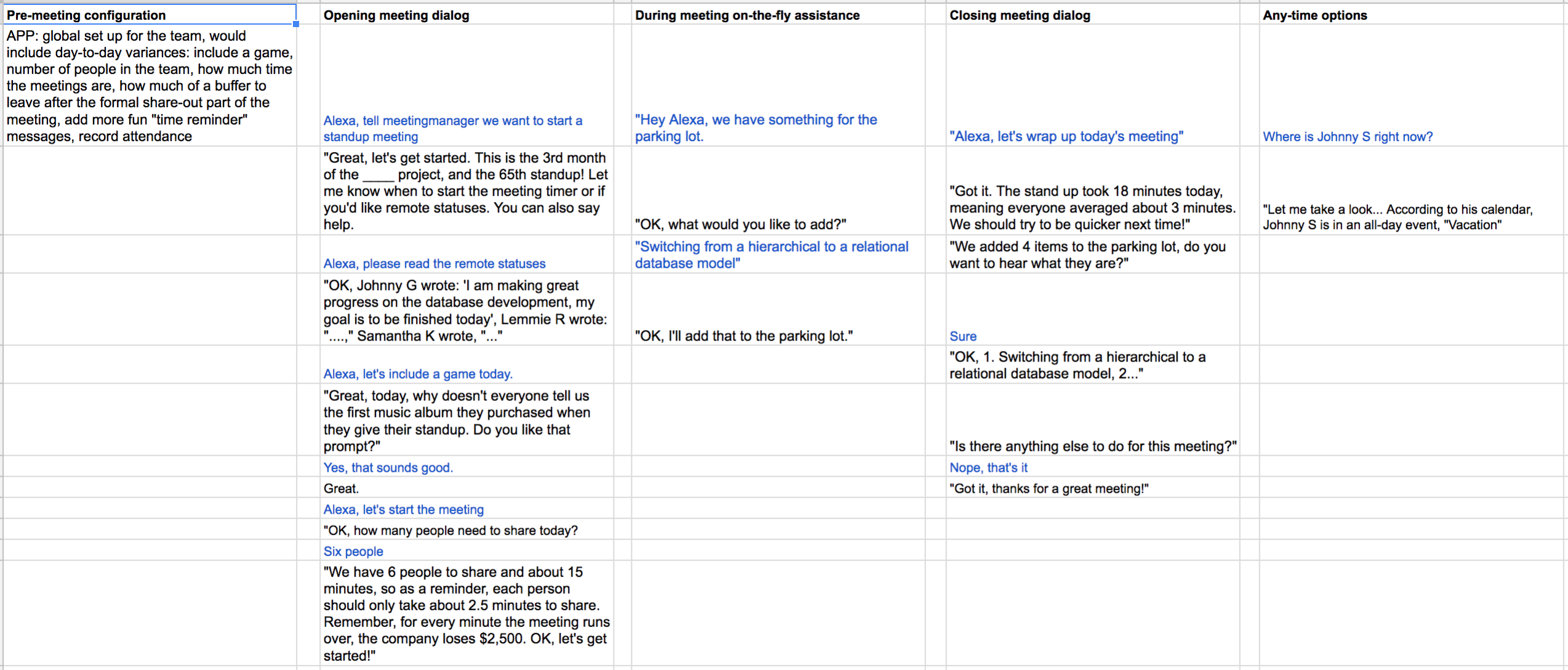

Since we’re designing a dialogue, it would make sense to use a script to model the conversation, right? For our Alexa project, we used Google Sheets to write a script that represent an exchange between Alexa (written in black below) and the user (in blue). Each column represents a scenario, like the start of the meeting for example.

The advantage of this script method is that it is easy for anyone to read and understand. The conversational flow between Alexa and the user feels natural. The interaction is easy to understand and evaluate as a whole, so it would be a good idea to use this format when you want to share your vision with stakeholders or clients.

However, it doesn’t leave a lot of room for complexity or specificity. Since it’s represented linearly in each column, there’s no room in the layout for divergent conversation paths. Most of the bot’s questions require “yes” or “no” responses from the user, but if there was, say, a third option or any follow up questions, we’re now in situation where we need to add another column or somehow link to an alternative conversation path.

Conversation flow

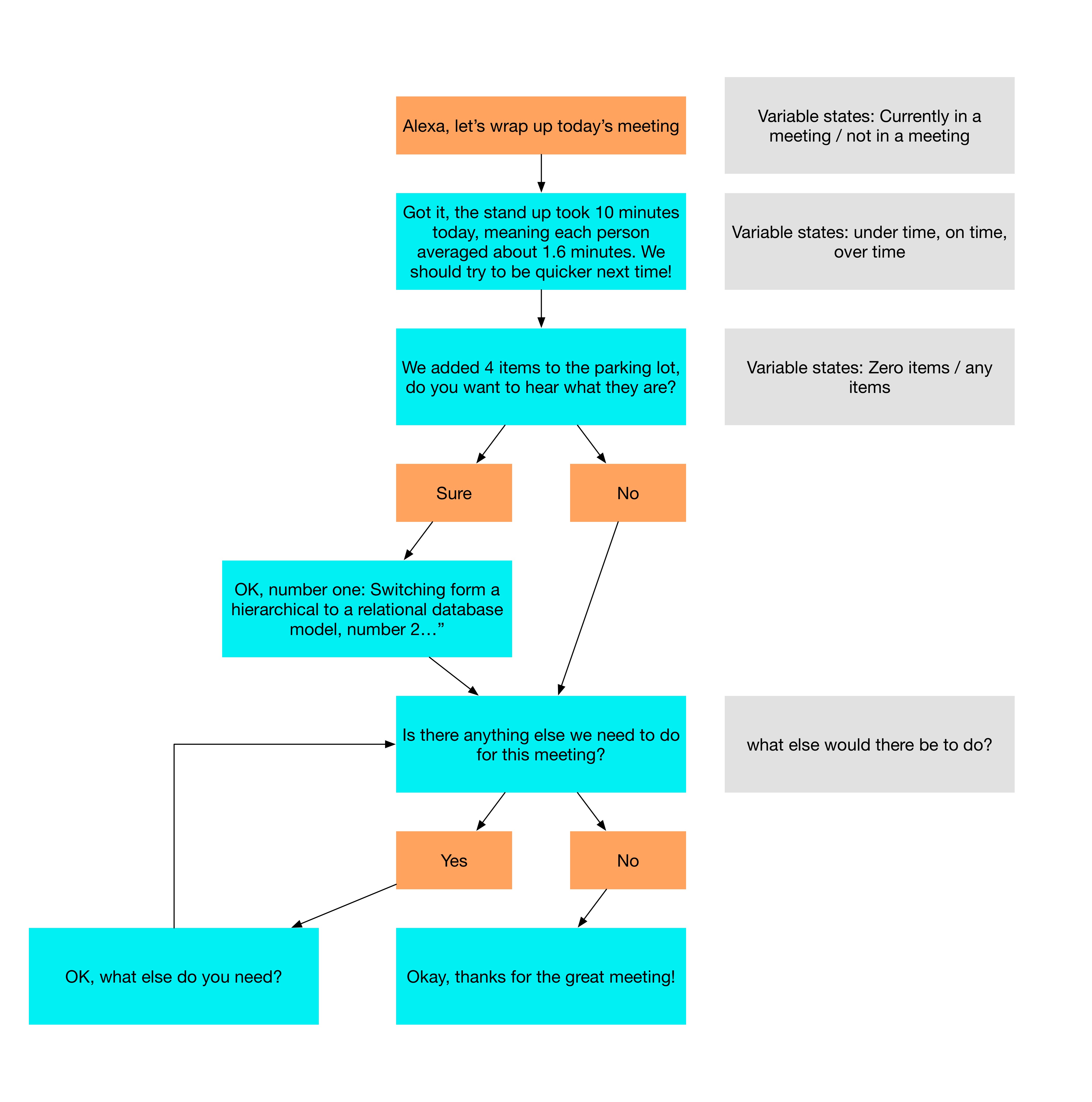

A conversation flow, modeled after a flowchart, is an elegant and obvious way to depict the entirety of a conversational UI, including multiple conversation paths. Below is the flow we created for our Alexa skill.

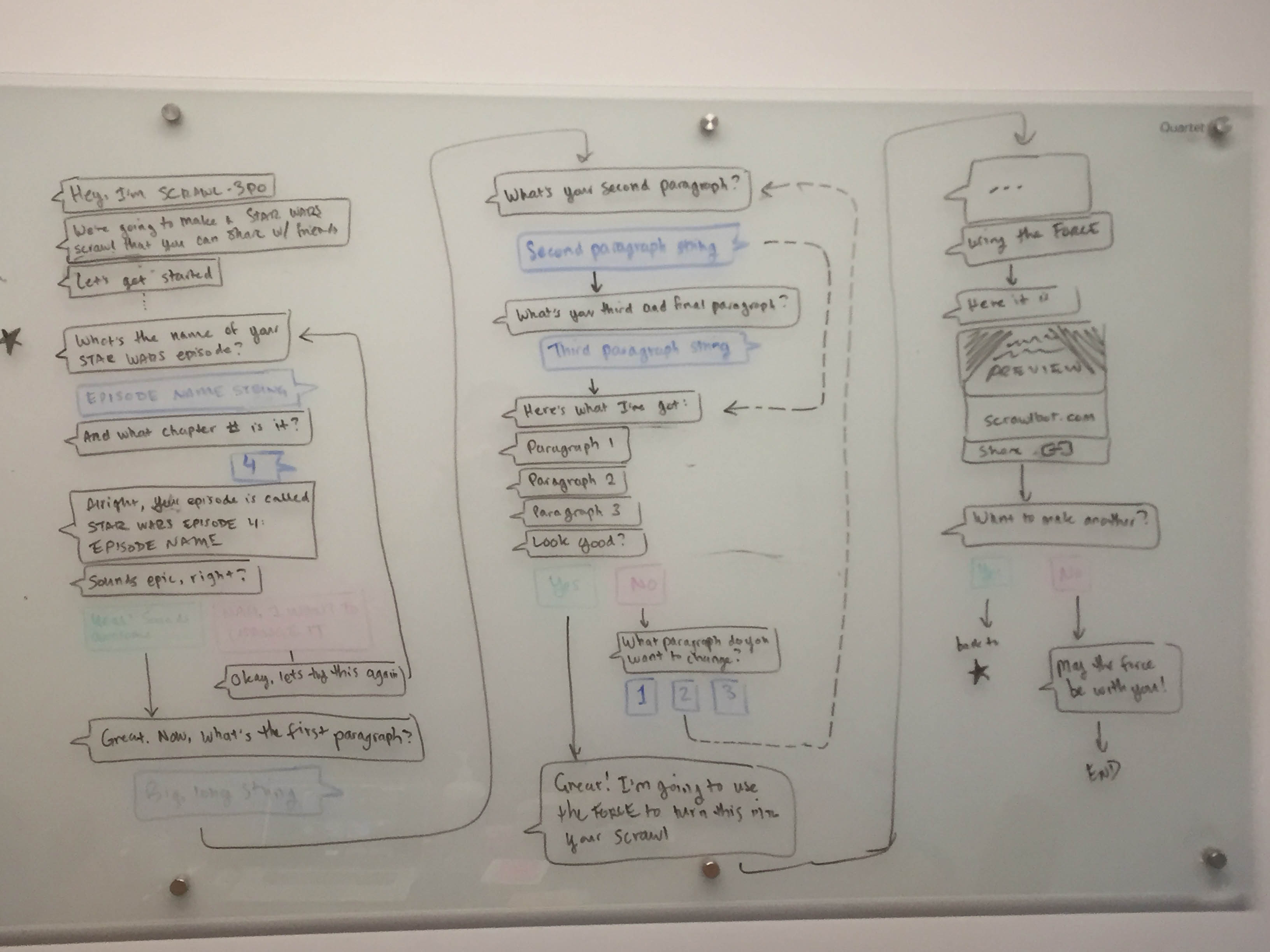

The visual nature of a conversation flow makes it a great option for planning the conversation, especially in the early stages of the project. I tend to use this method when brainstorming how a conversation will flow, since it helps to visually organize the entire interaction. The example below was created at the start of our Facebook Messenger project.

This example also demonstrates the downsides of a conversational flow. First, it’s a pain to make any major changes, especially if you want to add or significantly update a conversation path. It requires a lot of manual reorganization. This is a point of friction in the process, especially when it comes to sharing this with developers and keeping it up-to-date. Second, it’s not very modular. Conversation paths don’t make sense out of context, and there isn’t an elegant way to refer to another section of the conversation without a bunch of messy arrows.

I would suggest to use a conversation flow when brainstorming, or when summarizing the final version of the conversation as a high-fidelity artifact.

Modular method

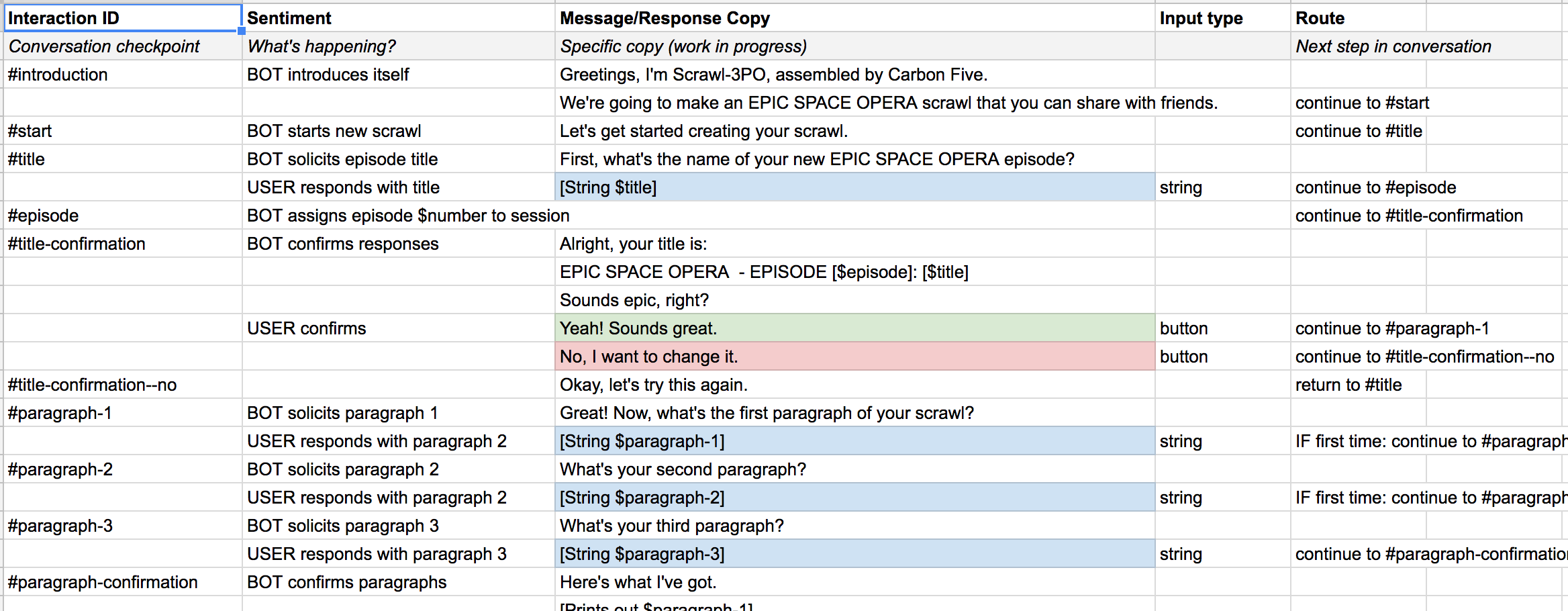

The final method, which I call a “modular” approach, breaks down the conversation into modular chunks – a sort of conversational checkpoint – which makes managing and updating the conversation simpler. In the example below, I used Google Sheets again to document our Facebook Messenger conversation.

I label with an Interaction ID. Each chunk contains a discrete exchange between the bot and the user, which I semantically describe as a Sentiment. Each Sentiment is has accompanying Copy, which is what the bot explicitly says and what the user responds with. I color code all user responses with green (the “yes” answer), red (for “no”), and blue (for neutral answers). Some responses become $variables, which the bot will refer to later. For each response, I specify an Input Type, like a string or a button. Finally and crucially, I specify a Route, which is where the conversation should go next. Here I refer back to the Interaction ID.

Of course, the modular method isn’t visually appealing and it certainly requires a high level of maintenance. But I’ve found that the use of Interaction IDs and Routes especially make it easy to change discrete sections of the conversation entirely without major reformatting or reorganizing. I’ve also found that by using developer-friendly concepts like #IDs and $variables, I can ensure a successful hand-off to developers.

Modularization abstracts the conversation from the actual copy (which can be changed and finessed separately), and allows everyone on the team to communicate clearly about the bot’s interactions. In fact, we referred to to the Interaction IDs in our user stories when building it. For that reason, I would suggest using the modular method mostly during the implementation phase of the project, especially when developers are involved.

Takeaways

The important differences between the methods I’ve described above are their utility during different phases of the bot project and the intended audience. Consider representing the conversation as a script when you want to share it in an easy-to-digest way and when you don’t want to represent every path the conversation can take. Use a conversational flow to summarize the conversation as a whole during early brainstorming phases, or when you want a complex, higher-fidelity representation of the artifact. Finally, use the modular method when the team is in the process of building, as it affords the best combination of flexibility and detail, especially to developers.