Product Management For Agile Teams: Why Oh Why

At Carbon Five, we build software. We build it using Agile methods. This has worked out well for us and our clients for a long time. We recently added product management as a discipline to our team. There are some common challenges we see at C5 and we’ve been deliberately experimenting with different activities and practices around product development, some of which we will be sharing in this series of blog posts.

Picture this:

Our team is working in a startup environment. Our product owner–let’s call him Alex–while business savvy, has no product management experience. He has a very clear and detailed vision of the product in its finished state. Complete with comps. Those designs, while beautiful, were not created in response to specific user problems; they’re a product of Alex’s brain alone. When our team begins work, questions arise. User stories are written against the comps, instead of against problem statements generated by research with real users. The comps are referenced, but a picture doesn’t necessarily speak the same 1000 words to everybody.

Design and development begin.

Design provides a solution that addresses their understanding of the user problem but that doesn’t match the product owner’s vision.Trying to get back on the same page, the designer incorporates features from the vision into the design, but they don’t really address the problem statement.

Weird things get built.

The developers have questions. Where will the data come from? What happens when conditions X and Y aren’t met? What if the entire internet collapses? So! Many! Questions! But there aren’t as many answers.

Development and design continue. Weird things get built.

Eventually the feature is delivered and the product owner is unpleasantly surprised. So! Unpleasantly! Surprised! Stories get rejected. Souls get searched.

Development and design continue. Weird things get built.

No one is having fun. What happened?

Well, one thing that happened here is that Alex didn’t realize that his vision, so clear in his mind, was actually incomplete. Or, at the very least, the version of that vision that was translated into user stories for the team did not completely capture what was in Alex’s head. Other people realized; that’s why the developers asked all of those questions. But this gap can be very challenging for a team to bridge.

When it came time to reflect on the project, the first question that came to mind was “Why?” Why is the team struggling to understand the thing we are trying to build? It seemed a little impertinent to ask it. But we did anyway.

You’re probably familiar with using 5 Whys for root-cause analysis. If not, using this technique you look at a problem and ask why it happened. Then you take the answer and ask why again. And again. By the fifth why, you should have moved beyond the symptoms to arrive at the real issue. In this case, we thought it might be interesting to modify this activity. Could we turn 5 Whys into an activity to discover and explore the problem statements a particular product design is trying to address?

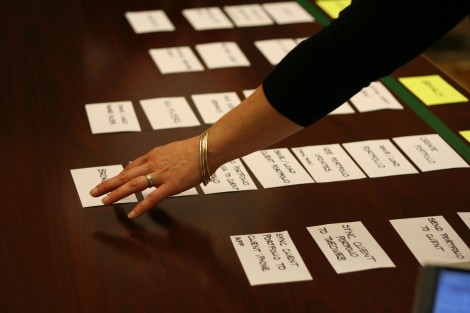

So we asked “Why?”. Why are we building this? But instead of honing in on one answer, we wrote down all of the answers on the whiteboard. Then for each of those answers we again asked “Why?”. Why is this important? And for each set of answers we kept asking “Why?”

It was important that we followed up on every answer, that we allowed the questioning to branch. What we expected to find at the top of each branch was a user with a problem. We started from a solution, our assumption was that it was solving something for someone.

Working backwards from the solution gives you the opportunity to, in a non-confrontational way, uncover the gap between the proposed solution and the problems you are trying to solve for your users. Once you’ve generated a list of reverse-engineered problem statements, you can start to ask questions about the goals of your project.

- Is this the problem we thought we were solving?

In our case, no, it wasn’t. As we moved away from our solution, we found ourselves in a land of nebulous, big problems. These problems didn’t fit comfortably with the solution we were executing.

So we could go on to ask more questions. Like:

- What are the implications for our business model if we solve this new problem instead?

-

Is this new problem a real problem? How do we know? How might we find out?

There are a few reasons this might happen. One might be that the problem you are solving has actually changed. Your solution has been rendered obsolete by additional research, feedback, changes in the marketplace or the advent of new technologies. Another reason might be more political. An executive, your product owner, or somebody else on your team has a pet solution and it is going to be employed no matter what problem you decide to address.

In our case, the big thing we discovered was that Alex was trying to “economize” on solutions. Seen from a certain perspective, this single solution addressed many of the problems the team had identified. But once the surface was scratched, it turned out the solution didn’t solve any of the problems adequately. It was a pretend solution for real user problems. This is why the developers and designers were having so much trouble grasping it.

Another result of allowing our questioning to branch during the 5 whys was that we found ourselves with several different problem statements. This may seem obvious, but this side-effect is a happy benefit. As soon as you have a list of things you can prioritize it. We had our product owner force rank the problem statements.

That led to an important insight: the priorities we had just identified were not reflected in the product backlog. Going back to the user problems and prioritizing those, rather than prioritizing solutions, allowed us to focus on the most important problems and design tailored solutions for them, rather than trying to make the highest priority solution solve as many problems as possible.

This approach allowed us to unpack the product owner’s vision by coming at it from a different angle. And it allowed the team the freedom to explore things that previously were seen as off-limits to questioning. We’ve described a situation where we did this exercise in response to a specific challenge. You could also run it proactively early in the project or when ideation begins on a new feature, especially if you know people have strong preconceived notions about the feature.

5 Whys can’t solve all your problems. But if you have them in your back pocket, they might come in handy in an unexpected situation.

Jeremy is a software engineer with 20 years experience. He likes making useful things that people need.

Janet is a Product Manager with experience in corporate, non-profit and consulting environments. Collaborating with developers is her favorite.